Amy here. I have recently returned to the CFA office after attending the 2016 Midwest Archives Conference in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Midwest Archives Conference, or MAC, is a regional professional association with over 800 individual and institutional members that represent all types of archives in the 13 heartland states and beyond. The association’s annual conference rotates its location yearly, and as Milwaukee is a quick train ride north, I took the opportunity to attend. I was looking to get an idea of the current state of archives in the region that CFA represents, it would allow CFA to be represented at the conference, and it would also be my first trip to Milwaukee!

CFA’s offical MAC credentials

During the conference I attended panels led by a variety of different archival professionals, all sharing perspectives on both their triumphs and failures in their workplaces. A few themes surfaced for me, the first of which was diversity and inclusion. A panel on promoting women in archival collections, a panel of archiving Midwestern immigration history, and the conference’s plenary session (with keynote speech from current Society of American Archivists President Dennis Meissner!) were amongst the settings where diversity and inclusion were explored. I appreciated the opportunity to hear attendees discuss this theme, as women and social justice are very present subjects in CFA’s collections.

Another theme that came through in the conference’s panels, an extremely relevant theme to all, was access. In listening to archival practitioners from organizations big and small, it was clear that all recognized the need for putting significant effort into making their collections relevant and available to their patrons. Also recognized were the challenges that came along with providing proper access. One panel titled “Playing Outside: Opportunities for Community Engagement Beyond the Archives” discussed the obstacles of rights, institutional permissions, and even rainy weather, in relation to getting patrons interacting with archival collections. A panel on oral history collections discussed making digitized and born-digital interviews searchable and accessible online with the very cool Oral History Metadata Synchronizer tool. As community events and online access are two crucial elements of CFA’s current operations, I was also grateful to get a perspective on access in the context of other workplaces and in the context of non-film collections.

The final theme I saw is a theme that has taken over the archives and film world: digital. A panel titled “I Jumped In, Now What? Keeping your Head about Water with Born-Digital Materials” discussed working through the discomfort of acclimating to a digital workflow for the first time. Another panel broke itself into discussion groups where the discussion leaders encouraged attendees to share their concerns, questions, and personal discoveries regarding digital initiatives and their archival work environment. CFA could definitely relate to this topic, especially in the wake of acclimating to the Kinetta Archival Film Scanner.

Plenty of other topics were covered in panels and happy hours over the course of the few days at the conference. Attendees also took advantage of museum visits, Milwaukee tourist sights, and meeting new friends in the archival community. It was exciting to learn about other collections, and it was invaluable to be able to share professional experiences with other Midwestern archivists.

Taking advantage of Milwaukee’s sights

While Amy was in Milwaukee, I (Brian) traveled to the land of our photographic founding father, Rochester, NY, to attend the George Eastman Museum’s Nitrate Picture Show film festival. The weekend-long event was a celebration of films produced on cellulose nitrate stock (the highly flammable material that was industry standard until about 1951), complete with ten screenings of original nitrate prints culled from archives around the world.

I stayed with former CFA staffer Lauren Alberque, whose cat Callie immediately took a liking to my NPS things.

One thing unique about the Nitrate Picture Show is that they don’t advertise the films they’re going to screen in advance. You don’t know what you’re going to see until you check in the first morning and get handed the program book with the schedule. This means you have to place a lot of trust in the programmers and archivists to pick films and prints that are worth traveling for and committing to. Now, the whole schedule is online, and you can see the impressive array of films, including Laura, Bicycle Thieves, The Tales of Hoffman, Road House, and more. The last screening, known as “Blind Date with Nitrate,” was kept secret until the curtain rose to gasps in response to Ramona, a gorgeous tinted silent film on loan from the Gosfilmofond of Russia.

Of course, the main draw of the festival is just how rare it is to see nitrate prints projected at all. The Dryden Theatre at the Eastman Museum is one of three theaters in the country still licensed to project nitrate, meaning they comply with safety requirements to contain any bursts of flame that might occur. Nitrate prints have to be shipped and stored in very particular ways, and the staff at the Museum spends days working on a single print to make sure it can be projected safely, testing everything from splices to edge damage to shrinkage (since every screening was clearly going to be 35mm, the print information in the program book instead focused on shrinkage percentage). During the screening of Brighton Rock, the projectionists stopped the film mid-reel just because they felt something was wrong and wanted to change the threading, even though everything seemed fine from the audience. When The Verge ran a feature on last year’s Nitrate Picture Show, their headline called it “the world’s most dangerous film festival.”

So why nitrate, if it’s so dangerous? This was the issue facing archives in the switch to “safety” film stocks, and for most, the solution was to copy the nitrate prints onto safety prints and then destroy the nitrate. As a result, most original nitrate films are lost, and many of the screenings this weekend were introduced with stories of how the prints being screened were only saved due to mishandling or flat-out lying about their destruction.

Some say there’s a special quality to watching a nitrate print projected, that the material itself elevates the images beyond other film prints—and certainly beyond digital. Whether this is really true or not was a discussion of some debate over the weekend, but there is no denying that screening nitrate is special in that it’s the way these films were designed to be seen. Filmmakers creating them were shooting on nitrate, processing on nitrate, and then projecting nitrate to audiences whose only experience was nitrate. To see films at the Nitrate Picture Show was to walk back in time and become a filmgoer in 1950, seeing the bright Technicolor of Annie Get Your Gun, or in 1947, entering the tough black-and-white world of Brighton Rock. There’s no other way to get as pure a cinematic experience when it comes to these films.

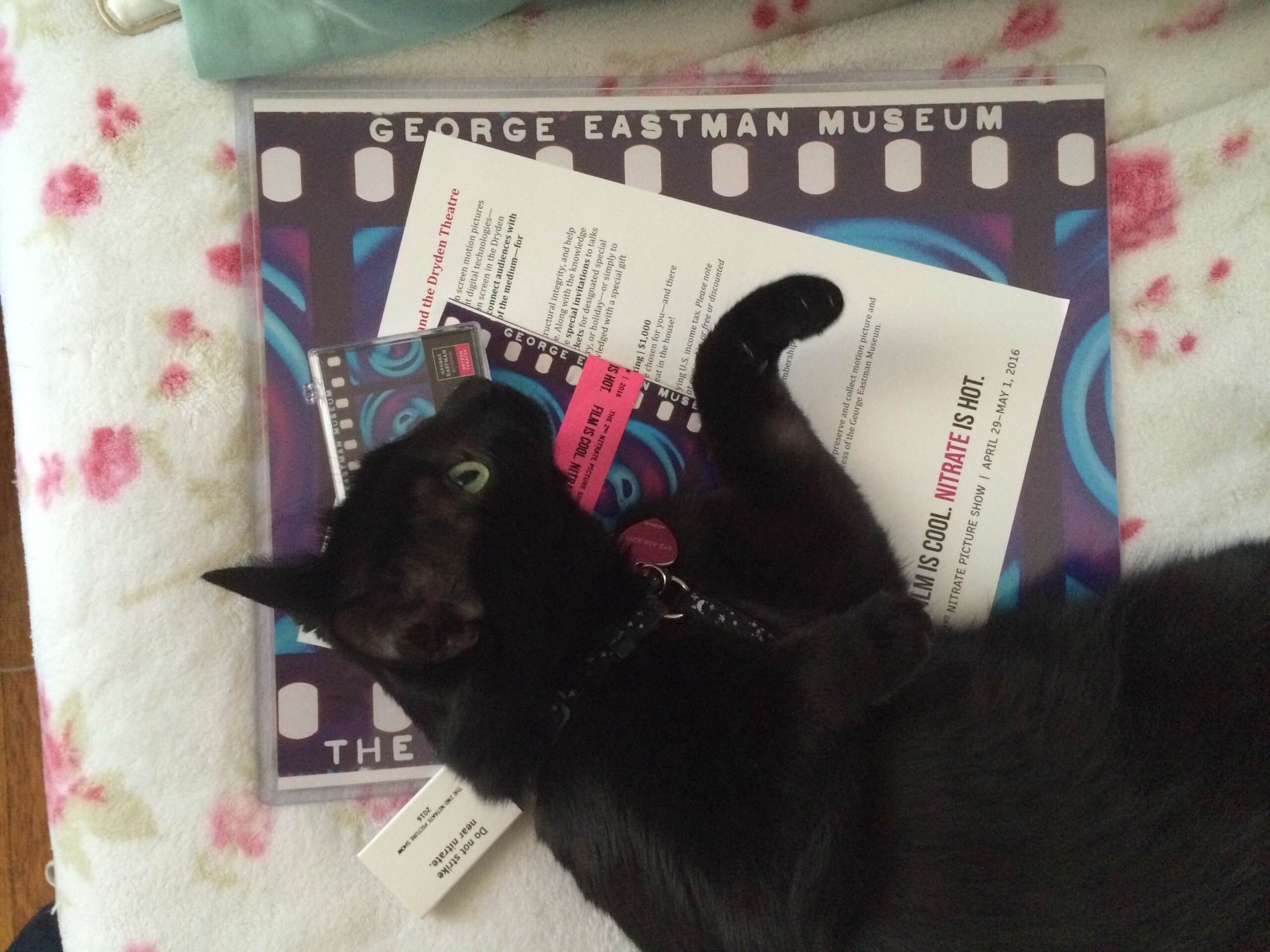

Myself, I was particularly taken with the swirling cigarette smoke in Laura and Road House, which took on a ghostly quality I hadn’t quite seen before, and immediately understood why the effect became such a staple in the noir genre. Other highlights included Enamorada, a Mexican film with stunning close-ups, and two animated shorts by Oskar Fischinger—An Optical Poem and Allegretto—with beautiful color. And I don’t think I’ll ever forget the theater singing along to the end of The Golden State, an animated short about the glory of California (also my home state).

In a weekend already jammed with screenings, the Eastman Museum also set up a variety of events and workshops designed to inform and spread the word about nitrate film conservation. I signed up for the festival too late for most of the workshops, including tours of the Museum’s nitrate vaults and a demonstration of how to produce nitrate. However, I did still get to look at a few nitrate prints that were on display, including footage of President McKinley’s inauguration, and there were plenty of people from around the country to meet and talk about film with.

Matchbook given to all attendees

![[Rudy Lozano]](https://www.chicagofilmarchives.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Lozano2.png)