Midwest Stories: Gordon Parks

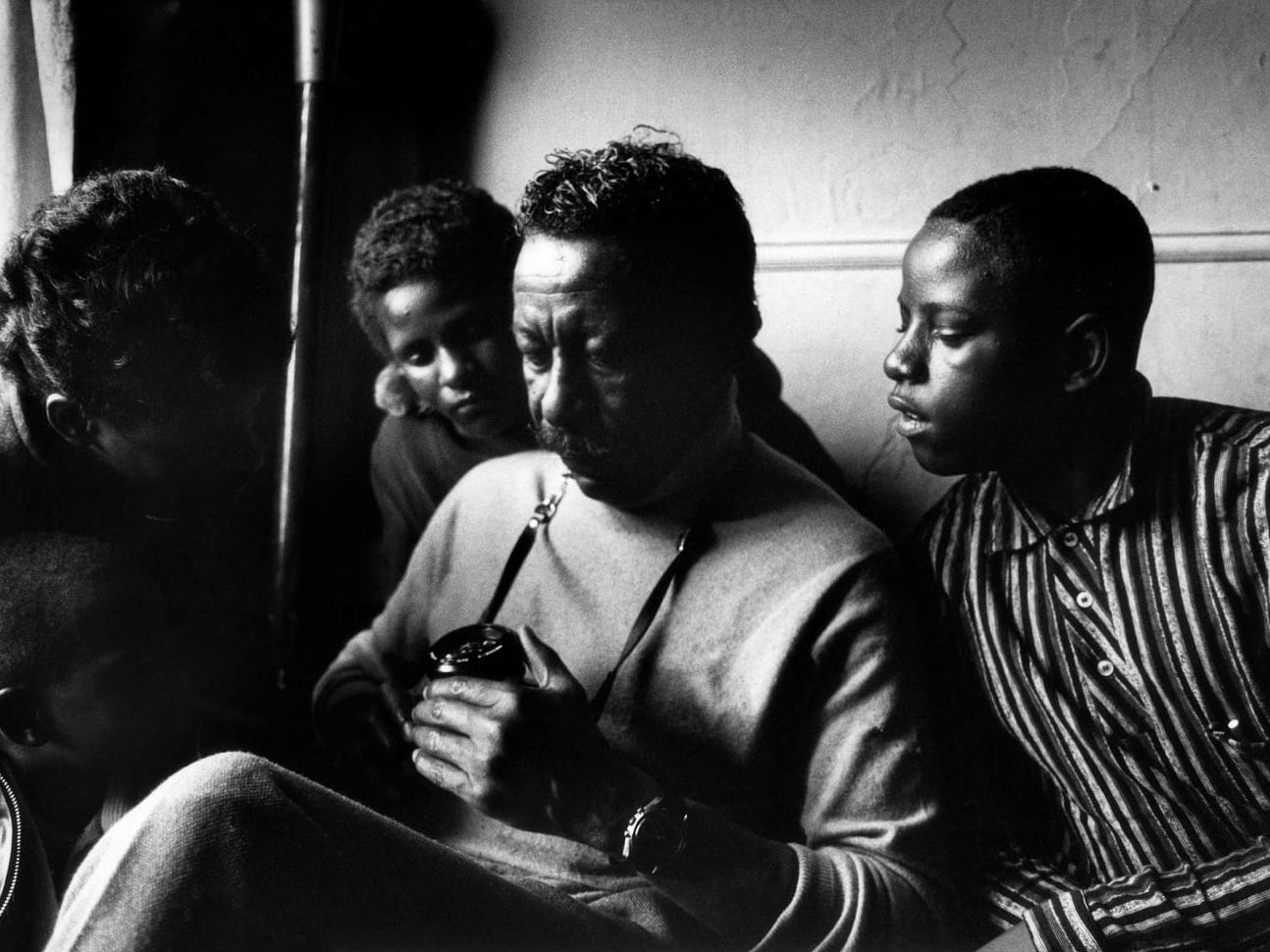

There is a striking moment in Gordon Parks’ sobering film, Diary of a Harlem Family (1968): Harry Fontenelle, whose recent arrest for drug possession triggers a spell in jail, is paid a visit by his parents. His mother, Bessie Fontenelle, with all the maternal sternness she can muster, tells her son that he needs to keep away from drugs and stay clean. Her son agrees, but he can’t promise her that he won’t ever touch the stuff again, stating with startling clarity that he never did heroin, only cocaine, which “isn’t too bad.” Harry realizes his mistake too late. Contrite and ashamed, he covers his face with his hand, while Parks’ vivid narration speaks to Bessie’s heartache, which in that moment lies just beyond the frame. While there are many remarkable images throughout Diary of a Harlem Family, this one image of a barely visible face covered by a hand heavy with grief and despair stands out. In this scene, as in so much of Parks’ work, there is a quiet struggle against erasure; an attempt to render tangible the pain of poverty, racism, drug addiction, and domestic violence.

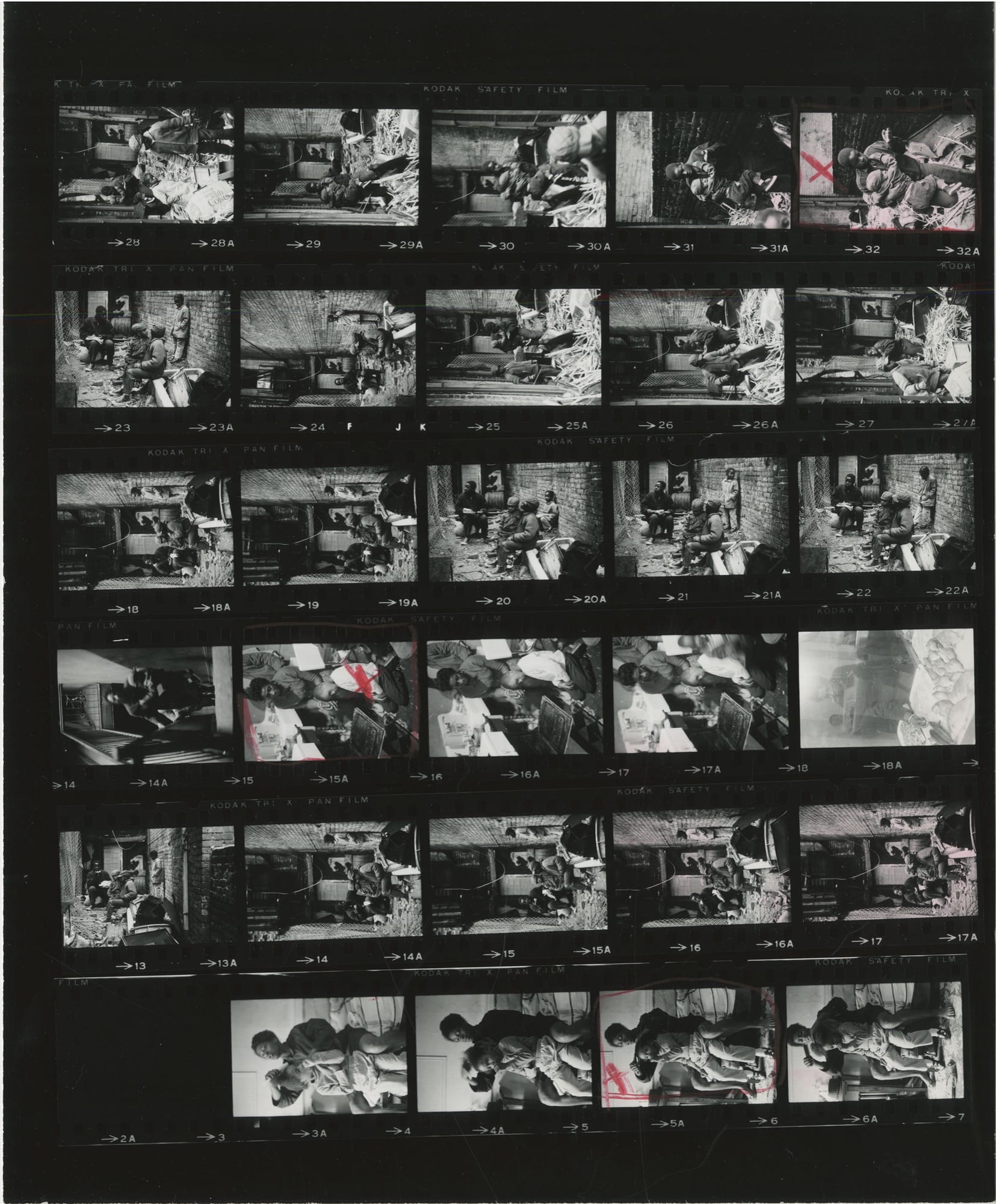

The short documentary is the culmination of Parks’ seminal photo essay for Life magazine, published in 1967, meant to shed light on the explosion of civil unrest in America’s inner cities. Parks aimed to document the vicious cycle of poverty and dehumanization through the lens of one family in Harlem. He lived with the Fontenelles for a month, diligently capturing their struggles through his distinctive photographic work as well as keeping a journal, which forms the film’s narrative spine. While the photo essay in and of itself proved groundbreaking, Parks felt that a film wouldmore accurately portray the family’s story. It is worth noting that for a documentary featuring voiceover narration, the narrator’s voice never overtakes the imagery onscreen, nor does it offer heavy handed manipulations of what the audience is viewing. Instead, it grounds the photographs, and provides an intimate glimpse into the bitter reality of life for families like the Fontenelles and other Black Americans in the country.

It would be difficult to overstate the influence of Gordon Parks’ oeuvre, which spans a variety of artistic disciplines from photography, filmmaking, music, and writing. An accomplished artist and humanitarian passionate about social justice, he brings the hidden narratives of so many to the forefront with unfailing integrity. While he would later live and work in other places throughout the country, much of Parks’ “origin story” emanates from his time in the Midwest, where he was born and first discovered his passion for photography, which led to the other artistic endeavors for which he is well known today.

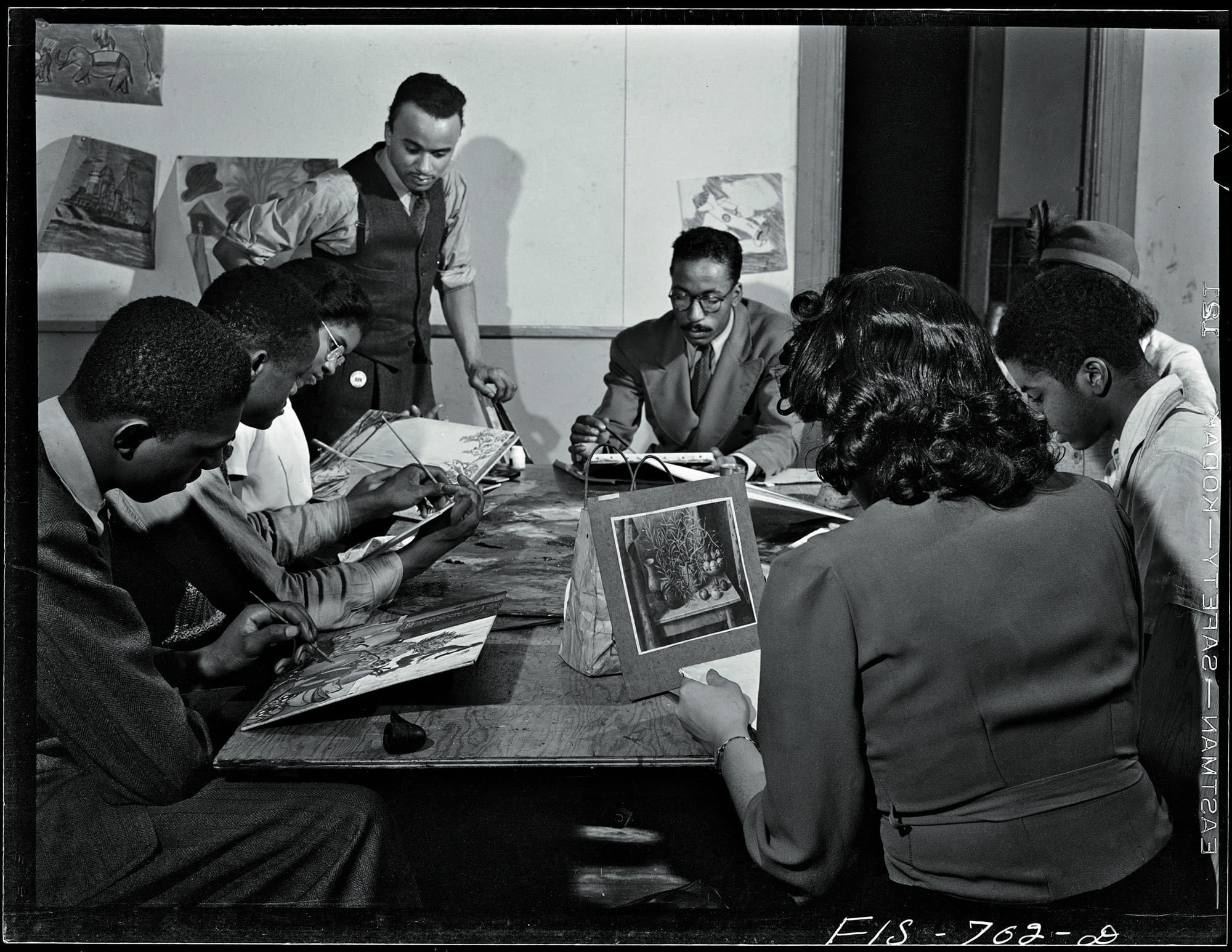

Born on November 30th, 1912, in Fort Scott, Kansas, Parks was the youngest of fifteen children. He describes his early childhood as somewhat rootless, especially after the death of his mother at the age of 15, which perhaps spurred part of Parks’ identity as something of a renaissance man. To keep himself afloat in his then-new residence of St. Paul, Minnesota, he would find gigs as a singer, a piano player at brothels, a busboy, and even found a brief stint as a semi-professional basketball player. But, he found his true calling at the age of 25, when he came across photographs of migrant workers in a magazine. He was taken by the camera’s capacity to tell the truth; as he would later say, “I saw that the camera would be a weapon against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point that I had to have a camera” (cite: GPF website). As he worked to teach himself the medium, he decided to move to the South Side of Chicago, and developed his own portrait studio at the South Side Community Art Center. He began chronicling the South Side’s Black community, and an exhibition of his photographs eventually won him a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for Photography. He worked alongside other major forces in the city’s arts and cultural scene at the time – including Dr. Margaret Taylor-Burroughs (who also founded Chicago’s DuSable Museum), painter Charles White, sculptor and graphic artist Elizabeth Catlett, amongst many others – all of whom laid the groundwork for Chicago’s Black Arts Movement of the 1960s.

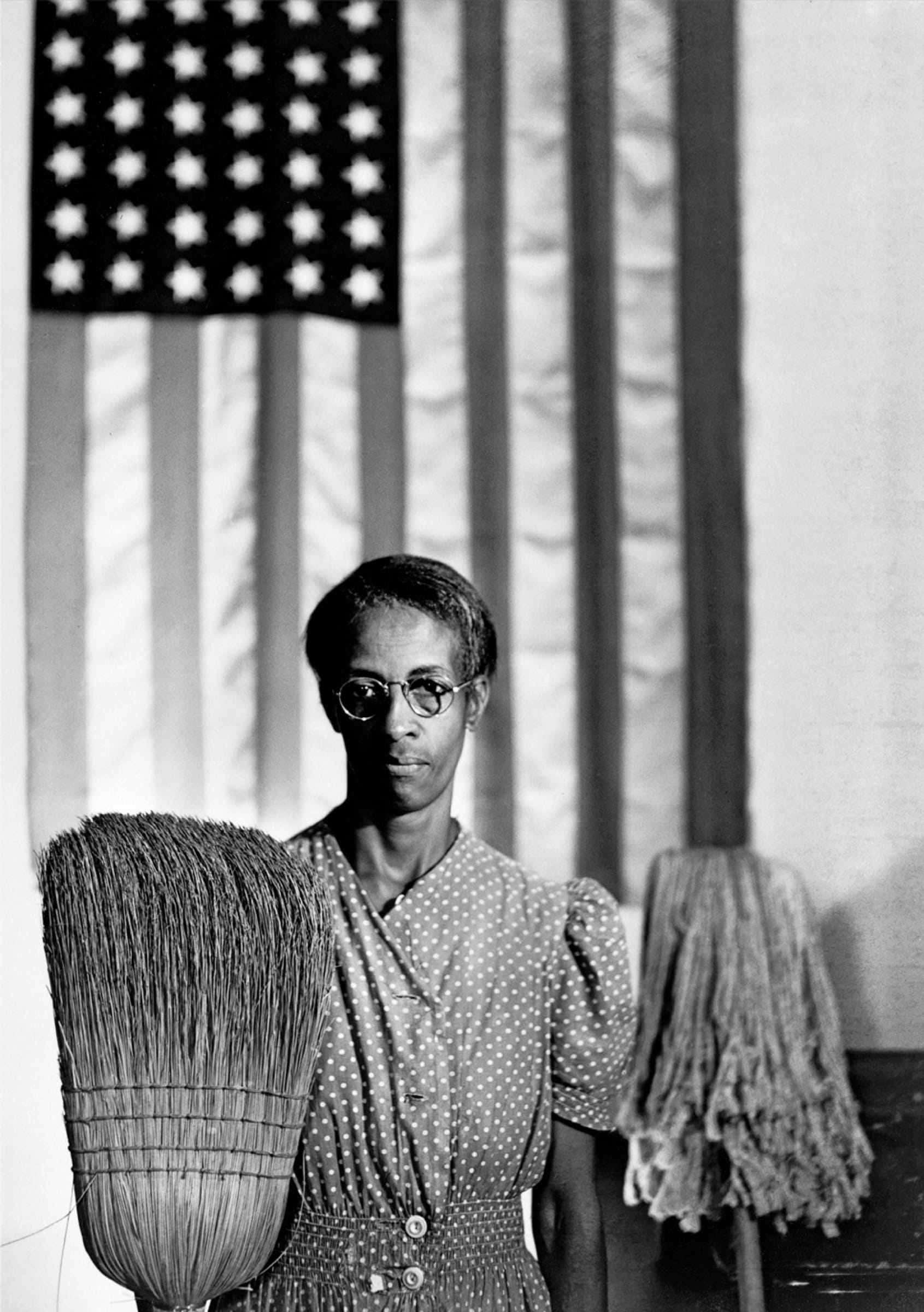

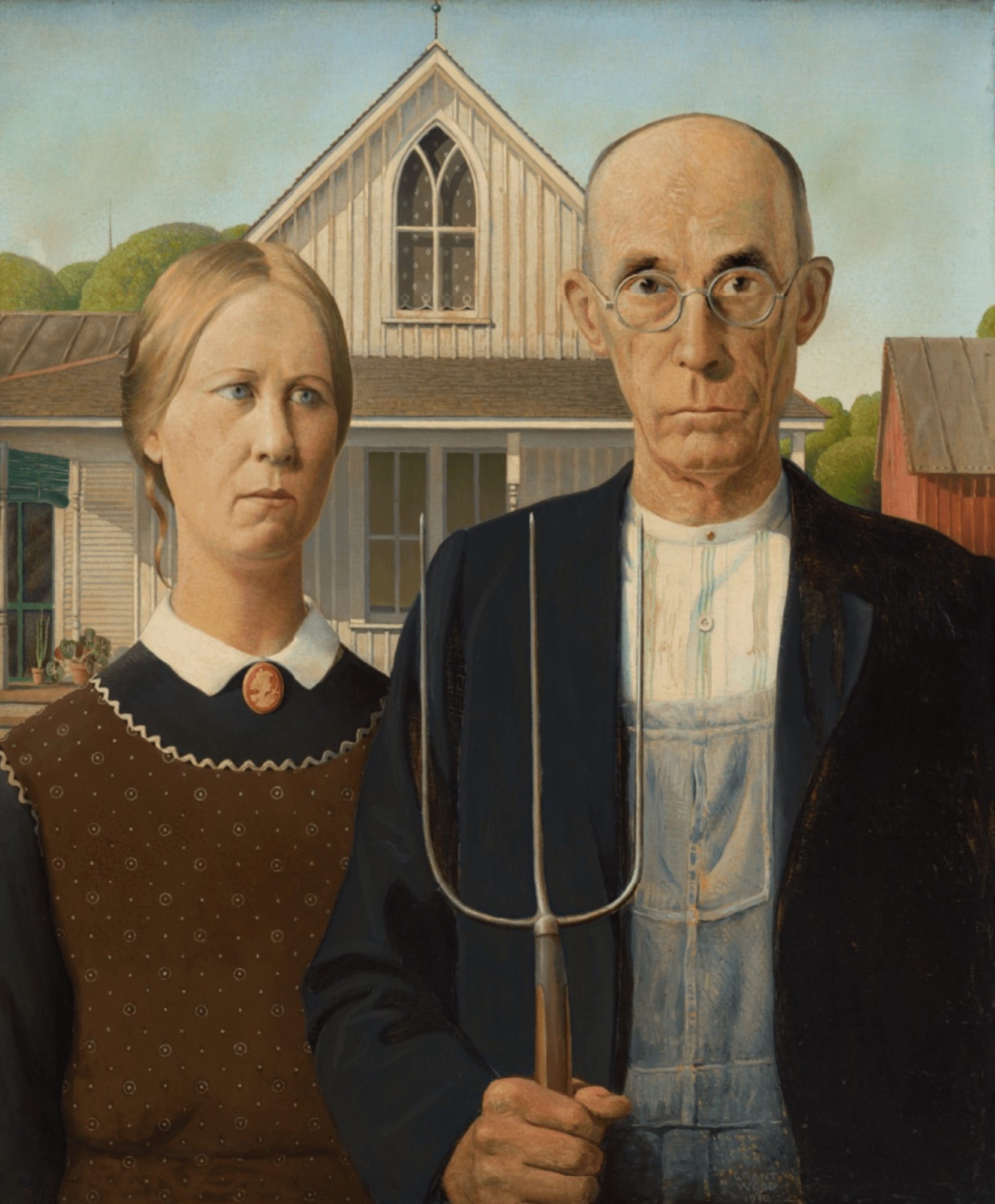

Due to his substantial artistic output in Chicago, Parks was able to secure an apprenticeship at the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in Washington, D.C., later becoming a correspondent for the Office of War Information. Working for the FSA must have seemed like a homecoming of sorts for Parks, since the evocative photographs of migrant workers captured by artists like Dorothea Lange (who was also commissioned by the FSA) helped initiate his quest to document the lives of the forgotten and marginalized. Parks’ most memorable photograph provided his own sardonic take on popular depictions of the Midwest in American culture. American Gothic (1942), is the mirror image of Grant Wood’s famous 1930 painting of the same name, which was gifted to and exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1930. Wood’s portrait of a solemn farm couple with pitchfork in hand is to some a celebration of the hardscrabble Midwestern character. Parks’ photograph is a portrait of cleaning woman Ella Watson, with mop and broom in hand, who represents America’s unseen and unconsidered workforce. Watson worked as a cleaner for the FSA, and the satiric commentary on Wood’s painting is impossible to miss. Arguably, the photo moves beyond the realm of parody, and can be seen as the inverse of Wood’s 1930 work: if American Gothic were turned inside out, you’d get Parks’ 1942 depiction. The difference is that the latter conveys an image typically erased from the country’s lore – the racism, the poverty – while the former upholds the well trodden stories Americans like to tell themselves.

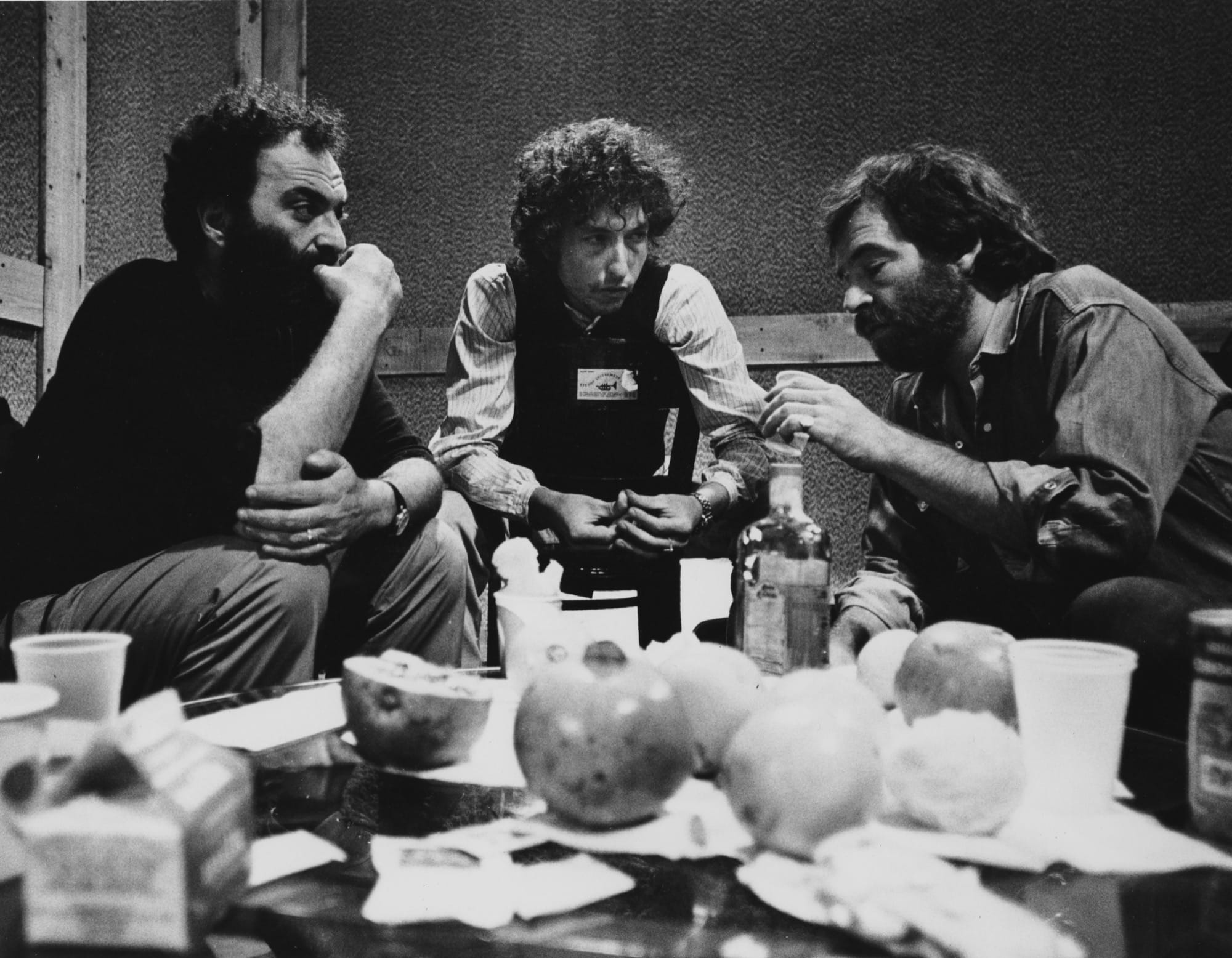

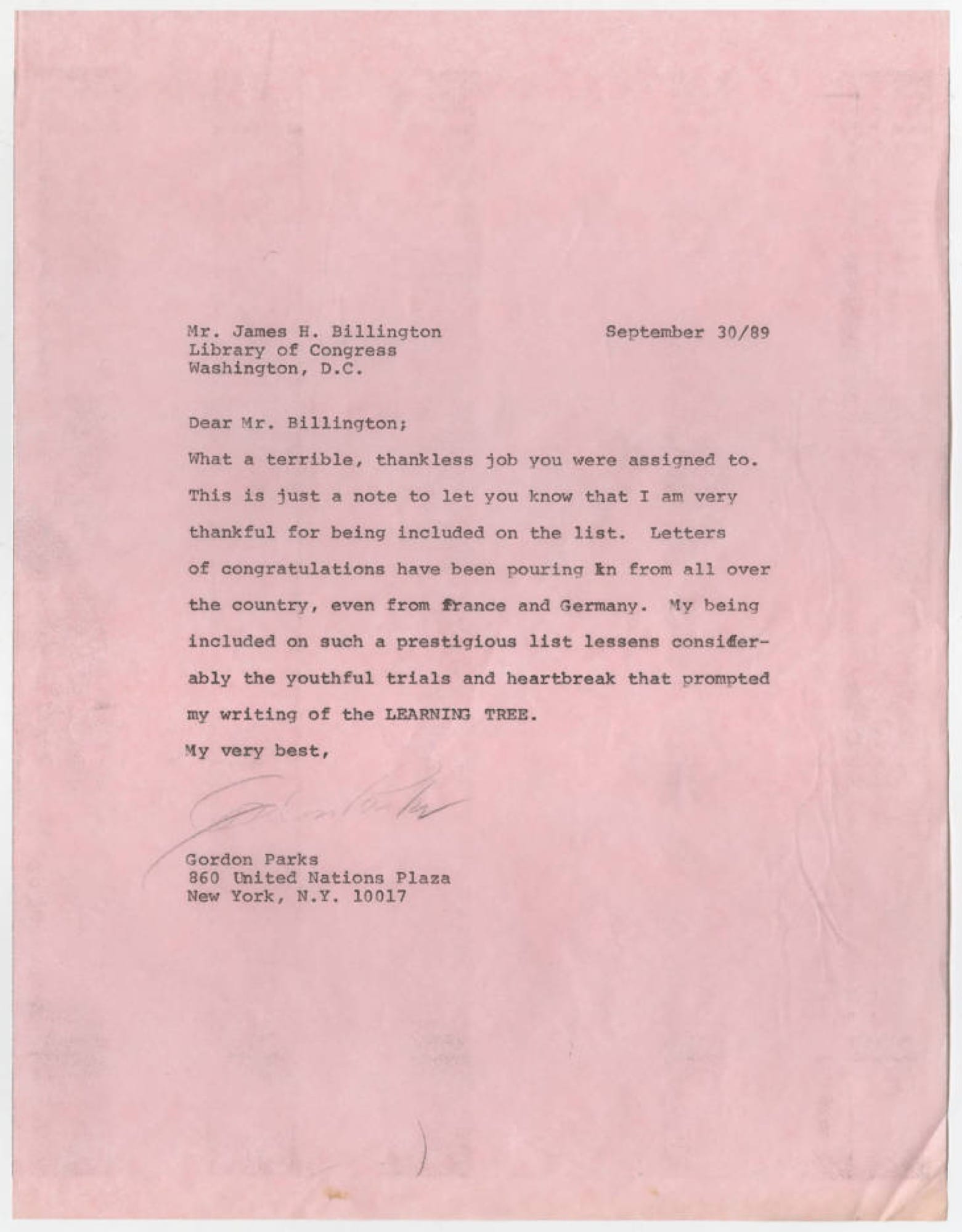

As Parks would remark later in life – despite his extensive travels, his consciousness remained tied to the Midwest; Kansas specifically. While technically Kansas was “liberated,” the effects of segregation and deeply entrenched racism could be felt in every area of his family’s life. Despite this, Parks could not help but long for his home, and for the possibility of a peaceful life on the family farm. He poured his yearning into a semi-autobiographical book based on his experiences titled The Learning Tree, published in 1963. The book was a critical and commercial success. With encouragement from fellow film director and friend, John Cassavetes, Gordon Parks wrote, directed, and scored a filmic adaptation of the book for Warner Bros. Studio in 1969, becoming the first black director to work at a major pillar of the film industry. The move to more mainstream and popular fare represented a major professional shift for Parks, and it would evolve to encompass perhaps his most beloved work, the iconic Blaxploitation classic, Shaft, released in 1971. Both Shaft and The Learning Tree were incredibly well received, and have since been included in the National Film Registry’s list of historically significant films.

Less well-known, however, are his films that preceded his Hollywood acclaim. Influenced by his early photographic work documenting poverty and racism in Chicago’s South Side, Parks turned to stories beyond the Midwest. His short documentaries Flavio (1964), The World of Piri Thomas (1964), and Diary of a Harlem Family (1968), are strikingly intimate portraits of individuals typically overlooked by society. Similar to Diary of a Harlem Family, Flavio began as a Life magazine photo assignment. Parks traveled to Rio de Janeiro in order to chronicle the life of people living in favelas, shanty towns hidden in the cities of Brazil. While there he developed a close relationship to Flavio, a wide-eyed 12 year old suffering from crippling asthma. Parks’ photo story led to thousands of reader letters as well as donations of over $25,000 to help pay for Flavio’s treatment. In the filmic version, Parks vividly captures the grueling poverty under which families like Flavio’s toil day in and day out. Every so often, his camera pans from the slums to a gigantic Christ the Redeemer statue looming ominously in the distance, covered in clouds – perhaps not a terribly subtle gesture, but a crushing indictment of social injustice all the same. In The World of Piri Thomas (1968), Parks turns his lens on the poet Piri Thomas, creating an impressionistic portrait of the countercultural figure. The made-for-television documentary brings to life Thomas’ groundbreaking memoir, Down These Mean Streets, published in 1967. The images of Spanish Harlem are haunting in their tenderness and violence: a mother is shown quietly feeding her baby, and elsewhere, someone inserts a needle into their arm. The documentary is unique not only in its portrayal of a part of New York typically not depicted on screen, but for its analysis of the city’s economic and racial fault lines, and the overall moral decay of a poverty-stricken Harlem. Thomas intones over the images “I’m a poet. I’m an ex-con. I’m a painter. I’m an ex-drug addict. I’m an ex-gang leader. I am a writer. I am a human being.” Parks highlights the humanity of all these individuals, giving voice to the voiceless, foregrounding their stories with grace.

Parks’ artistic vision is so broad and multifaceted that it can be difficult to categorize. His technical innovations in photography are numerous, to the extent that many of the aesthetic flourishes we see today can be traced back to Parks. Likewise, his films – both the more studio-driven, mainstream fare, as well as his compelling documentary work – have been remarkably influential. Artists today continue to draw inspiration from his films, from visual artist LaToya Ruby Frazier to rapper Kendrick Lamar whose music video for ELEMENT (2017) intentionally echoes Parks’ photo essays and work documenting the Civil Rights Movement. Parks’ output remains relevant and speaks eloquently to the current moment. When Chicago Film Archives first came into being, we were delighted to find 16mm prints of Diary of a Harlem Family, The World of Piri Thomas, and Flavio, donated to us by the Chicago Public Library (CFA’s foundational collection), as well as the Minnesota State University Collection. Since Chicago and the midwest region is so integral to the public’s understanding of Gordon Parks’ work, it seems serendipitous that we would house his films – particularly documentaries that focus on underrepresented narratives and communities. As a regional film archive, we are dedicated to rendering images and stories from our past accessible for a wider audience. This, in some ways, dovetails with Parks’ own work and we are proud to honor the indelible mark he has left on American culture. With the forthcoming 50th Anniversary of Shaft, Chicago Film Archives is happy to present with Anthology Film Archives and The Gordon Parks Foundation an online retrospective, THE WORLD OF GORDON PARKS: EARLY SHORT FILMS. Showcasing Parks’ early documentary films, the program will be available to stream for free from July 7th – 20th, and will also feature a 1973 documentary interview with Gordon Parks, Romas Slezas’ Listen to a Stranger, further contextualizing Parks’ remarkable filmic work. We hope you will join us!

Citations

1. The Gordon Parks Foundation, “Biography,” gordonparksfoundation.org

2. Diary of a Harlem Family,dir. Gordon Parks (PBL, 1968); see vimeo.com/201962649

3. The Art Institute of Chicago, “Gordon Parks,” https://www.artic.edu/artists/20027/gordon-parks

4. Swindell, Alissa. “A Living Institution: The South Side Community Art Center Celebrates Eighty Years as a Force in African American Art,” New City Art, https://art.newcity.com/2021/05/26/a-living-institution-the-south-side-community-art-center-celebrates-eighty-years-as-a-force-in-african-american-art/

Additional Resources

- https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2012/11/gordon-parks-remembered/

- https://wichita.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15942coll8/id/373/

- http://si.edu/Search/Index/default/1?q=

- https://www.artic.edu/artists/20027/gordon-parks

- https://art.newcity.com/2021/05/26/a-living-institution-the-south-side-community-art-center-celebrates-eighty-years-as-a-force-in-african-american-art/