This past summer, CFA was lucky enough to have Maggie Sivit as an intern. Amongst other things, she crafted the finding aid for the Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter Collection for us. Here is what Maggie had to say about her experience creating the finding aid:

Two months ago, I arrived at Chicago Film Archives as a summer intern. One of the projects I worked on during my time at CFA was the development of a finding aid for the Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter collection.

What is a finding aid?

A finding aid is a kind of research guide to a particular collection. It is a compendium of records of the works, organizations, and individuals associated with a group of films. It typically includes an abstract and overview, which answer questions such as: What films are included in this collection? When were they made, for what purpose, and by whom? Additionally, a finding aid includes metadata (e.g., geolocation tags, Library of Congress Subject Headings, production dates, etc.), access and restriction information, and media samples.

Why are finding aids important?

Finding aids are useful to researchers, as well as to anyone who wants to learn about the collections in an archive. Without these records, films might be archivally preserved, but no one would know anything about them or how they related to one another. (Furthermore, unless you visited the physical archive, you might have no idea that they existed.) A finding aid communicates a body of work clearly and succinctly; it provides a collection with context and coherence.

How is a finding aid created?

Creating a finding aid is essentially a process of cataloguing. Cataloging is an act of gathering and organizing (or reorganizing) information. At its most basic level, cataloging a film collection involves creating records, populating these records with information, and linking these records to one another in the appropriate ways.

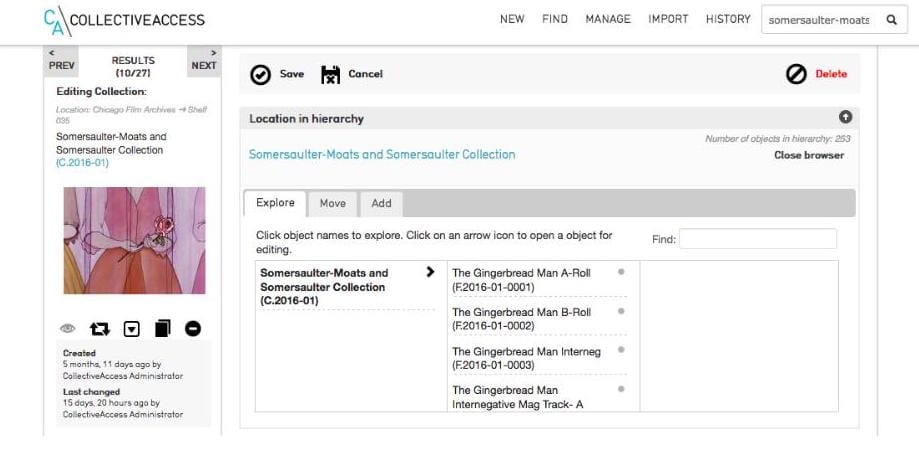

CFA uses a data management system called Collective Access to digitally manage its collections. Each collection is initially arranged in a hierarchical database model, which organizes data into “trees”, or “parent-child” relationships. Each item (a “child” of the “parent” collection) received upon accession is given a corresponding digital record. Under the Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter collection, the “child” nodes consist of all 253 items (master prints, internegatives, audio reels, etc.) that arrived with the collection. This mirrors the way the physical items are grouped in the vault.

Hierarchical organization of Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter collection, as seen from backend of Collective Access. Much dry, so boring.

This is not particularly useful to researchers (nor members of the public), who do not normally need or want to know about every duplicate print, A- and B-roll, internegative, or spliced segment that arrived in a canister, box, or bag.

Consider that the Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter collection totals 253 items. This includes 11 different film reels associated with the film The Silverfish King (“Silverfish King A-roll”, “Silverfish King B-roll”, “Silverfish King Print #1”, etc.). That is a lot to slog through — especially when you multiply this (or a similar number) by 30 works.

To begin cataloging the collection, I knew that I would need to create a record for each of the works. Additionally, I would need to create another type of record — called an “entity” — for several organization and individuals (production company, filmmakers, etc.) that were new to CFA’s database. Then, I would continue fill in the records by writing abstracts, descriptions (for works and the collection) and biographies (for people and organizations). Finally, I would link all of these together by creating relationships within the database.

Creating work records

The first thing I did to begin assembling the finding aid was to create a work record corresponding to each work in the collection. In total, I created 30 work records for the Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter collection. (Again, while there are e.g., 11 items associated with the film The Silverfish King, there will be only 1 work record.)

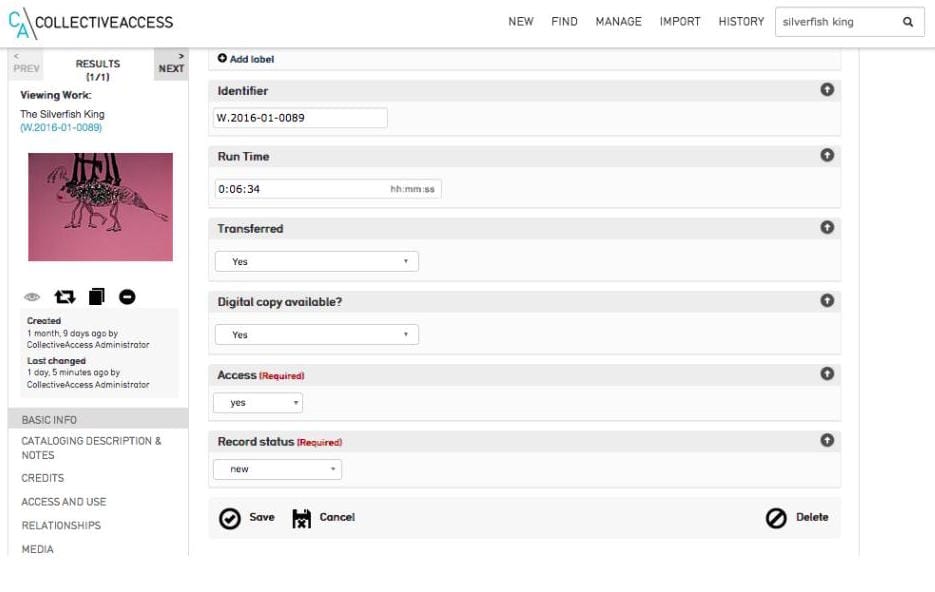

Work record for The Silverfish King, seen from backend of Collective Access.

Unlike item records, which treat films as physical objects (a reel inside a canister stored on a shelf in the CFA vault, subject to certain principles of damage and deterioration, etc.), work records treat the films as viewable works. A work record is broken into the following categories, each of which contains a set of fields:

- Basic info (e.g., Identifier, Run time, Digital copy available?)

- Cataloging description and notes (e.g., Production date, Abstract, Description, Language, Genre, Form, Subject)

- Credits (e.g., Sponsor, Main Credits, Additional Credits, Corporate names)

- Access and Use (i.e., who can view the work and how they may use it)

- Relationships (related works, items, entities, collections, and series)

- Media (stills or streaming files, if the work has been digitized)

Subject headings

One of the most important steps in populating a work record is “tagging” works and collections with subject headings (under “Cataloging Description and Notes”). Subject headings enable people to search for films by subject matter (“Domestic life”, “Industry”, “Lake Michigan”), genre, and form, and is a powerful tool for researchers. CFA uses two subject indices in its work records: a controlled vocabulary tailored to CFA, and the Library of Congress Subject Headings.

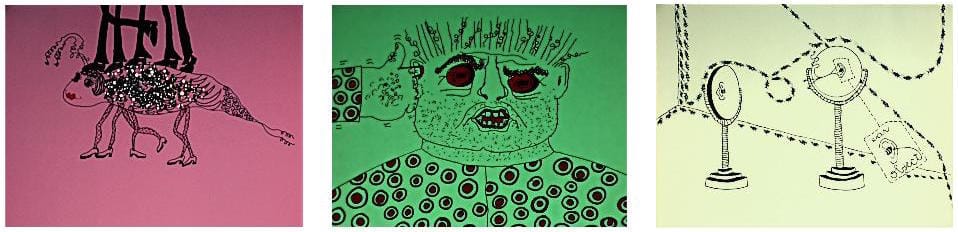

Let’s look at an example: The Silverfish King, a short film by Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter. Over fanciful, doodle-like drawings of an animate insect embarking on various adventures, a narrator describes the way that his childhood fascination with a silverfish morphed into a phobic obsession.

Scenes from The Silverfish King

Based on keywords from that description, “Bug”, “Insect”, “Silverfish”, “King”, “Childhood”, “Obsession”, and “Phobia” are all plausible tags for The Silverfish King. However, if you are searching for films about “Kings” or “Childhood”, this film is unlikely to be at all relevant. (This is one of the problems with keyword indices, which is what most web browsers — and many databases — use.) Even “Bug” and “Insect” are dubious; the film is about a bug (kind of), but it is not really about bugs. A more appropriate subject heading might be something like: “The logic of thought”, or “Irrational fixation”. Unfortunately, neither of these is available in the CFA vocabulary; furthermore, both are so specific that they are unlikely to apply to other films. The closest I could get was: “Imagination”.

This brings us to the matter of a controlled vocabulary. The fields into which subject headings are entered are not free-form text fields; they are “multiple choice” fields that restrict you to a limited set of terms. While the CFA vocabulary is quite specific, the Library of Congress vocabulary is so extensive as to sometimes be unwieldy. (Some issues that came up while I was applying Library of Congress Subject Headings: After tagging several works with “Fairy tale”, I realized that there was a separate heading for “Folk tale”. What was the difference between a fairy tale and a folk tale? (Had to look it up.) (Then, there was: “Fable”.) Should Briar Rose be tagged “Brother’s Grimm”, if it was far from the version that appeared in that original collection?)

This may seem like hair splitting, but tagging films by subject (and genre, decade, form, etc.) is in many cases what allows people to discover them. The difference between tagging a film as “Fairy tale” and “Folk tale” — or not tagging it at all — could be the difference between that film being used in screenings, exhibitions, research papers, and academic texts in the future — or simply being enjoyed by generations to come — and not.

Creating entity records

The database builds on its relational capabilities in other ways. Beyond works, there are entity records that must be created and linked to the collection. Normally, these entities include the filmmakers and production company(ies).

One reason to create entity records in addition to work records is that doing so allows you to build a more robust network. A filmmaker who donates her collection to CFA might also have acted in or produced films in other collections; because of the way that relationships are created in the database, all of these films can be linked to that individual. This allows you to see relationships across films and collections — across Chicago, the Midwest, and the twentieth century — more plainly. (It also allows you to search the database by individual, and ensures that you have the most complete filmography.)

I started by creating entities for Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter (Entity>Organization), Lillian, and JP (Entity>Individual). Eventually, I also created ones for Michael and Pajon Arts — a name that appeared mysteriously at the beginning of their more experimental films, and which turned out to be the original corporate name under which JP and Lillian worked.

Writing descriptions

By the time I began describing works and entities, I had already watched all the films (several times); read synopses of selected works provided by the filmmakers; read reviews of works (when I could find them) published in journals and newspapers; studied a list of awards, festivals, etc.; and read several articles about the filmmakers and production company.

The Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter collection was unusual, insofar as the filmmakers provided CFA with a great deal of biographical information when they donated the films. (I would not have known, otherwise, that Lillian was born Patricia Hewlitt and JP was born John Sauer; this became useful when filling in their entity records, which includes a field for “Alternative name” — allowing you to locate individuals even if you are searching with a maiden name, alias, etc.)

The more I learned about the filmmakers, the better oriented I became when looking at their works. (For instance: I learned that JP studied creative writing, and Lillian studied painting; after college, she worked as an apprentice to a muralist. Knowing this, I went back and watched the films again, paying attention to the credits. I began to be able to identify when JP had written a film, when they had co-written it, when Lillian had drawn the animations, when they had collaborated, and when the animations had been drawn by JP.)

Once I had read through all of this information, I felt like I could finally begin describing the individuals, organizations, works, and the collection itself. I could link all of the works and entities to one another as appropriate, by creating relationships within the database; and I could do all this only because I had spent a certain amount of time becoming immersed in their world, trying to understand how everything held together.

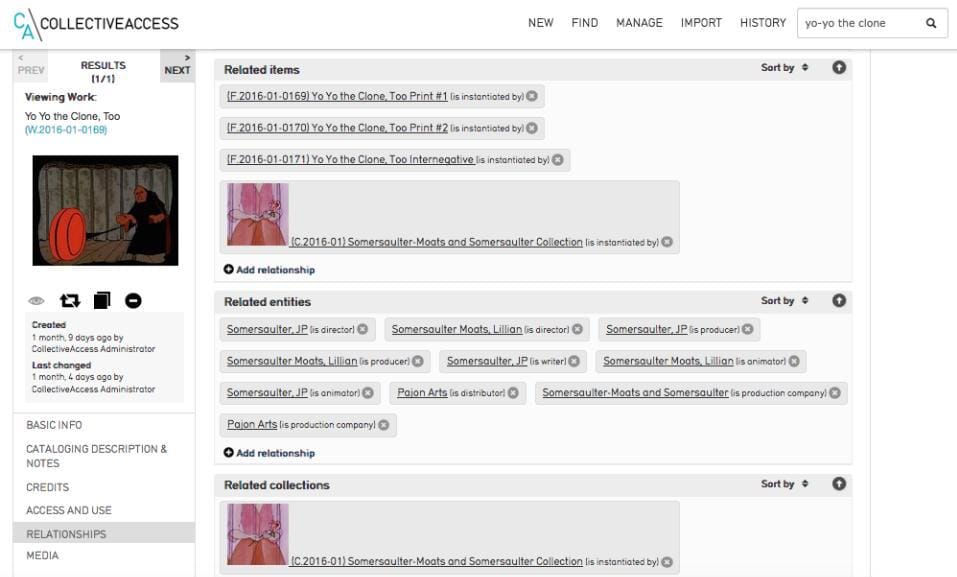

Work record for Yo-Yo the Clone, Too and various items, people, organization, and collection records as it is linked to through the relational database, seen from backend of Collective Access.

With all of these record elements completed, I clicked “Publish” — making the Somersaulter-Moats and Somersaulter finding aid accessible on CFA’s website. You can see it for yourself (and learn more about JP Somersaulter, Lillian Somersaulter Moats, and Michael Moats) here.

An archive is a place dedicated to storing and preserving historical objects — in the case of CFA, films. At the same time, an archive is equally dedicated to preserving the stories surrounding those objects: who made them, when they were made, where, how, and why. It’s a side of archival work that doesn’t get talked about very often; it’s mostly done on a computer, and involves creating records, writing descriptions, and organizing information. To me, it feels a lot like detective work; you have evidence (films), which you identify, record, and analyze, and from which you begin piecing together a picture — adding new people, seeing new relationships, and sometimes being led in unexpected directions. In the end, you present your findings as an account of what happened: an interconnected story — a finding aid — that holds the pieces together.

— Maggie

![[Rudy Lozano]](https://www.chicagofilmarchives.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Lozano2.png)